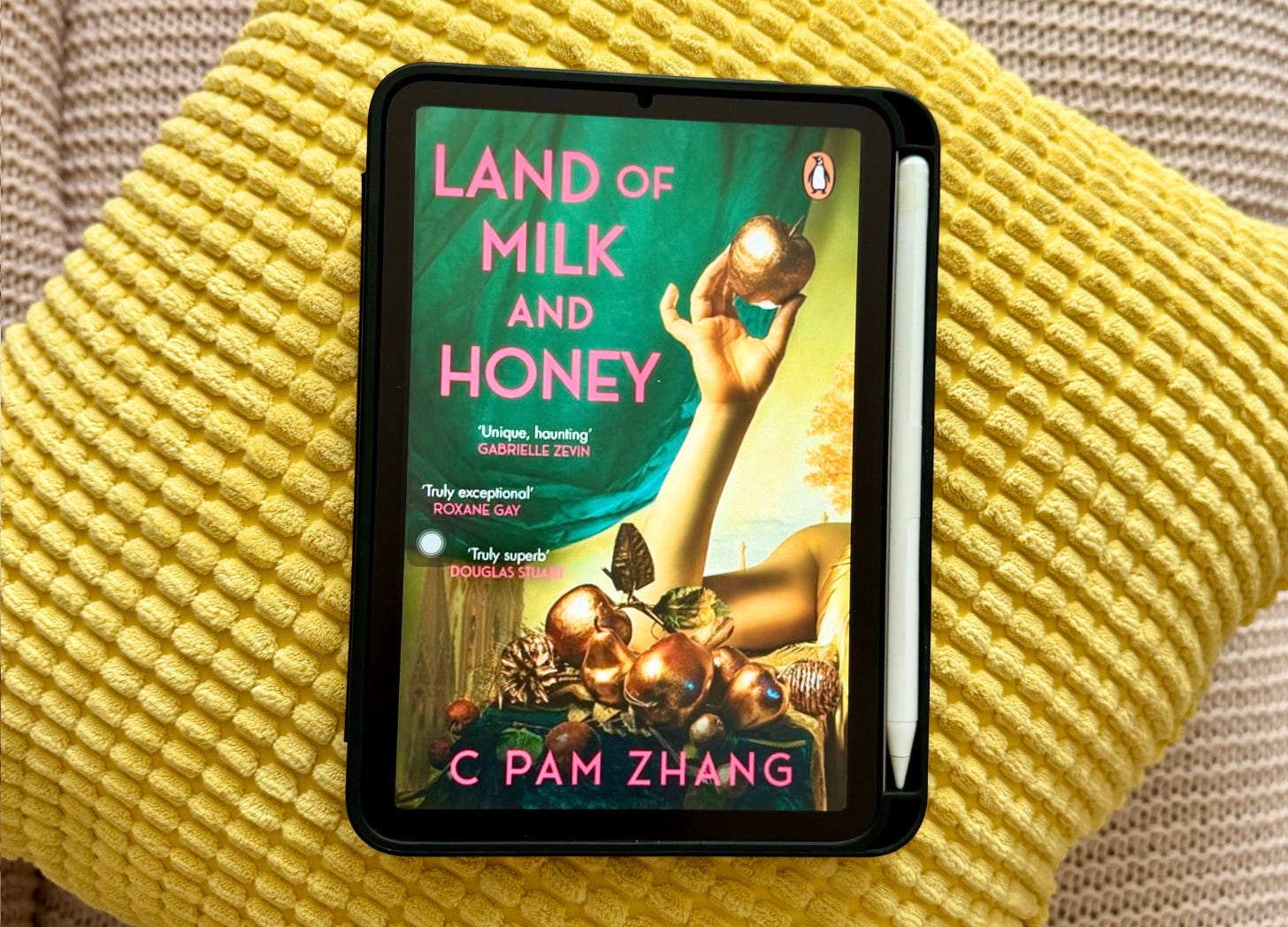

Land of Milk and Honey by C Pam Zhang | book review

A chef navigates survival, desire, and decadence in a smog-choked dystopian world

It happened again: I wanted a short palate cleanser and ended up reading a dystopian book. Let’s not psychoanalyse this.

Land of Milk and Honey is by C Pam Zhang, whose 2020 debut novel How Much of These Hills Is Gold was one of Obama’s favourite books of the year.

In this book, she returns to an arid setting. The narrator is an unnamed chef in her 20s an…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Reads With Alicia to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.